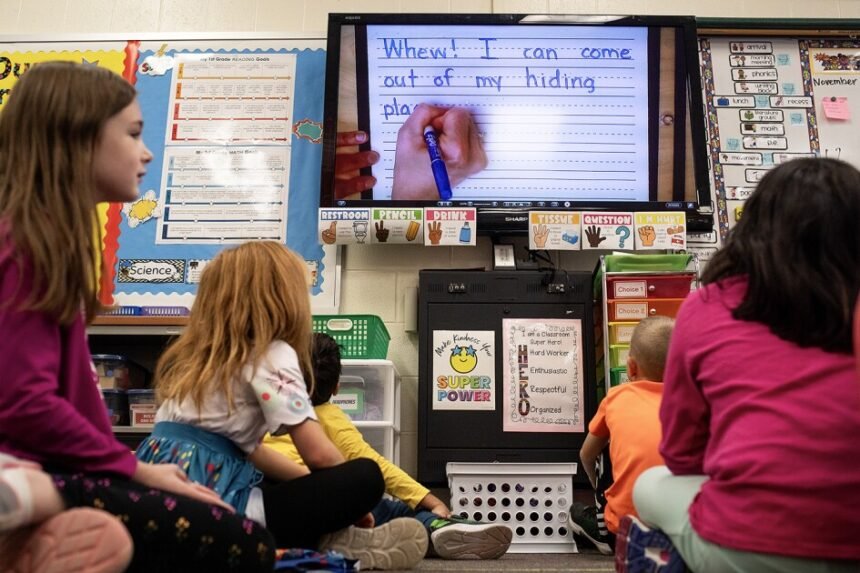

At New Lisbon Elementary School in Wisconsin, it used to be difficult for principal Stephanie Moore to keep track of what students in each grade were learning from one year to the next.

The school used a core reading curriculum, but teachers made a lot of their own adjustments, supplementing with other materials of their choosing. That meant that at the end of the year, Moore said, students’ reading abilities were all over the map, with different patterns of strengths and weaknesses depending on which teacher they’d had.

“When you’ve got three different teachers teaching the same grade level, and they’re pulling different resources, students are getting different things,” Moore said.

That’s one of the core challenges of mixing and matching reading programs and other materials in the classroom—a practice that data show is more common now than it was before the COVID pandemic.

Two new reports both come to the same conclusion: Teachers and school leaders are piecing together multiple resources. A recent survey from the RAND corporation found that the average teacher uses five supplemental resources, up from about four in the 2018-19 school year. In a separate survey, from the Center for Education Market Dynamics, almost half of school district leaders said that teachers used two or more programs in English/language arts classes.

The patterns raise new questions about how instruction is designed. Many researchers and education consultants warn against supplementing core programs in this way, arguing that it can water down the rigor of the curriculum for students and is logistically complicated for teachers.

But in surveys, teachers say they need the flexibility to make complex material more accessible for their students, who can come into the classroom at a wide range of different ability levels. And not all of the core programs districts choose are of the highest quality—some teachers say they need the option to bring in evidence-based resources when their schools don’t provide them.

The debate over whether to supplement a core program, and under what conditions, implicates central tensions in the teaching profession: How much autonomy should individual teachers and principals have? And how can educators balance the goal of holding all students to grade-level standards, while also offering multiple entry points into challenging lessons?

“We’re really aiming at the consistency between classrooms,” said Moore. At New Lisbon Elementary, teachers still use pieces from several different programs, but now under a unified plan from school leadership.

“Nothing’s perfect,” said John Humphries, the district’s pupil services director. “There’s good pieces of the puzzle in different places.”

The tension between preserving teacher ‘individuality’ and instructional coherence

Teachers have long augmented the curricula provided by their schools—adding in extra practice opportunities for students, putting their own spin on lessons, or even quietly setting aside the officially sanctioned resources in favor of ones they prefer.

Over the last two decades, the rise of online lesson-sharing sites, such as Teachers Pay Teachers, and open educational resources, freely available materials that teachers can augment and remix, have made it easier than ever to source supplemental materials.

The reasons teachers seek them out are manifold. In a 2022 survey, teachers said that the materials their schools wanted them to use weren’t engaging enough, didn’t differentiate lessons for students at different levels, and didn’t have enough support for students with disabilities—even when outside rating organizations had deemed these resources high quality.

And for years, some educators have argued that requiring classroom teachers to follow anything too tightly controlled, a “scripted” curriculum, robs them of their ability to exercise professional judgment.

One Connecticut teacher described her district’s move to a scripted curriculum as “heartbreaking” in a 2022 interview with Education Week.

“We kind of lost our individuality,” she said at the time. “I relish making up a lesson. I relish doing some research, trying to make it fun. … Districts are focusing too much on the science [of teaching] with data and test scores, … and we have really lost sight of the fact that it’s [also] an art.”

But there are trade-offs to relying on teachers to create or search for lessons, said David Steiner, the executive director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy and professor of education at Johns Hopkins University.

“Most of the stuff on Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers is chaotic and wildly unorganized,” he said.

Steiner is an advocate for what are often referred to as “high-quality instructional materials”—core curricula that have been given high marks by external reviewers. These programs can require students to take on demanding work, and several states and districts that have pushed their use have seen student gains.

Some students will likely need extra support as an “entry point” into grade-level work, Steiner said. But that should be targeted to the most important prerequisite skills, not comprise a general review of below-grade-level content. Many of the free resources circulating online don’t make that kind of distinction, he said.

There are some research-tested tools made for this purpose, designed to be used in tandem with a core curriculum. Steiner referenced Zearn, a math learning platform that maps lessons to the Common Core State Standards, as an example.

Targeted use of a supplemental program like Zearn could make sense in a classroom where many students are below grade level, he said.

This distinction is one that resonates with Taryn Rawson, the principal of Goldrick Elementary School in Denver.

There, teachers supplement the core curriculum in 4th and 5th grades with additional work on decoding multisyllabic words and studying morphology, the structure and meaning of word parts. The practice helps students decode the more complex, subject-specific words they encounter in these upper elementary grades, Rawson said, but those routines aren’t included in the core curriculum.

She sees this schoolwide strategy as different from telling teachers to pick and choose whatever materials they think would work best.

“If I walked into a classroom in a literacy block and a teacher was supposed to be in the middle of a [core lesson], and I saw some word searches with a Teachers Pay Teachers logo on them, that would be a conversation,” Rawson said.

Why some districts say they need multiple programs

Getting teachers to adhere to a core curriculum, of course, relies on leaders providing high-quality materials to begin with. In many schools, that’s not the reality.

As the “science of reading” movement has spread across the country, more schools have adopted English/language arts programs for early elementary school students that align with the evidence base behind how children learn to read.

But as of 2022, at least a quarter of teachers said their schools still used programs that incorporated practices that reading researchers have said could make it harder for children to learn to decode words, according to an EdWeek Research Center survey.

In some districts, leaders have chosen to add a supplement in foundational skills—such as phonics and phonemic awareness—to curricula that don’t offer systematic, explicit instruction in those areas. Sometimes that’s done explicitly to “patch” weaker materials.

Leaders in the New Lisbon, Wis., district wanted to adopt an evidence-based approach to foundational skills, but their existing core program, a basal-style reading curriculum that aimed to build reading skills through short text excerpts wasn’t strong in this area, said Moore, the elementary principal.

Buying an entirely new comprehensive program would have been “very, very expensive,” she said.

Wisconsin has promised districts partial reimbursement for choosing one of its state-approved curricula, but that money isn’t available yet. So last school year, New Lisbon adopted a phonics and phonemic awareness supplement, switching it into the district’s reading curriculum in lieu of that program’s foundational skills lessons.

Even when districts have purchased new curricula rated “high quality,” leaders’ decisions about what makes the cut don’t always line up with teachers’ perceptions about what will best serve their students.

In New York City, for example, where elementary schools are required to adopt one of three reading curricula that the city says are aligned to the science of reading, some teachers have criticized their schools’ choices, Chalkbeat has reported.

Soliciting teacher feedback early in the curriculum-selection process can prevent educators from feeling the need to augment the program later on, said Mackenzie Sheahan, the director of K-8 curriculum and professional development in the Portage schools outside of Kalamazoo, Mich.

Three years ago, when the district started looking for a new reading curriculum, leaders were hoping to find one that met their criteria across the board, Sheahan said. But they couldn’t find one that had both a strong foundational-skills program and approached comprehension instruction the way they wanted—focusing on building students’ knowledge and incorporating diverse texts.

So they went with two different programs: one knowledge-building ELA curriculum, and one foundational skills supplement.

“We got more teacher buy-in by finding the right tools for the job,” Sheahan said, “rather than getting a one size fits all and forcing them into it.”