As the “science of reading” movement has grown, more districts are moving away from reading programs featuring practices that aren’t supported by research, and toward programs that are rated highly by external organizations, data show.

But many school system leaders still report that they’re instructing educators to use multiple programs together, or supplementing their core offerings with add-ons—suggesting that even “high-quality” instructional materials aren’t meeting all of educators’ needs.

These findings, from a survey of 1,553 school districts by the nonprofit market-intelligence organization the Center for Education Market Dynamics published in July, portray a curriculum landscape in flux. The reports’ authors caution that using bits and pieces from different curricula without a clear strategy in place could lead to all of them being less effective.

But that doesn’t mean that careful approaches to combining resources is necessarily a problem, said Lora Kaiser, the center’s executive director.

“Any of these choices may or may not be good depending on what you want teachers to accomplish,” she said. “What are the supports provided by districts to ensure that’s executed effectively?”

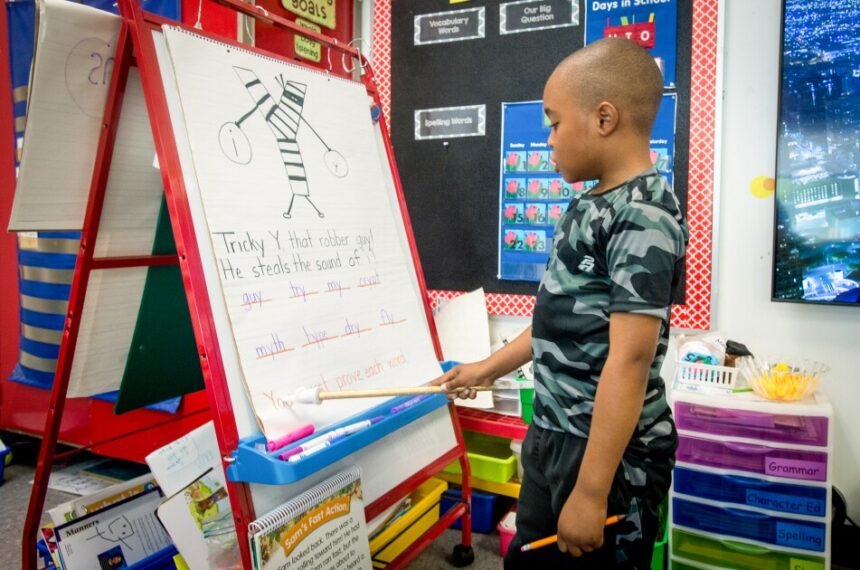

Having a clear plan is key, said Brent Conway, the assistant superintendent of the Pentucket Regional school district in West Newbury, Mass. The district uses Great Minds’ Wit & Wisdom, a core ELA curriculum that doesn’t systematically teach foundational skills like phonics on its own. It’s designed to be used with a foundational-skills supplement. Pentucket uses the University of Florida’s UFLI program.

A program designed to support students’ language development and writing ability, like Wit & Wisdom, relies on different principles of best practice from a program designed to teach students letter-sound correspondences.

“They need to function differently,” Conway said. “I don’t see an inherent problem in mixing and matching; however, you need to understand the intentionality behind them.”

Top programs rank highly on EdReports, see mixed reviews elsewhere

Survey data show a continuing shift away from programs that multiple curriculum reviewer organizations have said aren’t likely to support struggling readers.

The market dynamics center’s sample includes districts from the organization’s nationally representative dataset, as well as what the group calls its “impact core,” a collection of large districts that together serve more than half the country’s students.

About 9% of these districts were using Heinemann’s Units of Study for Teaching Reading in the 2023-24 school year; that percentage dropped to about 6% in the 2024-25 school year. Use of Fountas & Pinnell Classroom dropped from 4.2% of districts to 2.8% during the same time period.

The most commonly used curricula among survey respondents have received high ratings from EdReports, a nonprofit curriculum reviewer that evaluates materials for alignment to the Common Core State Standards and several other factors, including usability.

The most popular are McGraw Hill’s Wonders, Benchmark Education’s Benchmark Advance, HMH’s Into Reading, and Amplify’s Core Knowledge Language Arts.

These programs have been included on several states’ lists of approved materials for evidence-based reading instruction—a possible explanation for their rise in popularity—in part because of their top marks on EdReports, which states often base their evaluation criteria on. Still, some researchers and educators have contested elements of these programs that they say don’t reflect best practice.

Student Achievement Partners, a nonprofit educational consulting group, published a mixed review of Wonders in 2021, authored by a team of reading researchers. Reviewers said the program was “overwhelming” and bulky, “a significant issue that dilutes its many strengths.”

The Reading League, an organization that advocates evidence-based literacy instruction, has dinged Into Reading for practices it says don’t align with reading research, such as teaching children to memorize whole words without attending to letter-sound correspondences.

It makes sense for districts to rely on reviews that highlight the criteria that are important to them, said Kaiser.

“As consumers, we live in a world where we triangulate all kinds of data and information when we make our purchases,” she said.

Almost half of districts say their schools use two or more programs

Whatever districts choose as their core curriculum, though, many educators are likely using it in tandem with other resources, the market dynamics center data show.

Forty-eight percent of the districts reported using at least two resources in ELA classrooms. This group was split into two categories.

In the first category, comprising about 19 percent of districts, schools used two core programs—curricula that are designed to serve as the anchor for an ELA lesson, usually incorporating multiple components of reading instruction, such as foundational-skills work and comprehension.

For instance, one of the most common combinations cited was Into Reading, a basal-style program that uses excerpts specifically organized for teaching reading, and Core Knowledge Language Arts, a “knowledge-building” curriculum that intentionally integrates social studies and science topics. Other districts reported using both an English and a Spanish version of the same curriculum in bilingual programs.

In the second category, which included 29% of districts, schools used a core program with supplemental materials: resources that target one component of reading or one set of skills and are meant to be used in concert with a comprehensive curriculum. About half these districts said they were using four or more supplemental resources.

This could look like a district using Wonders, another basal-style core program, alongside two foundational-skills supplements: Wilson’s Fundations and Collaborative Classroom’s SIPPS. (Districts relying on supplemental foundational-skills products were most likely to use Wonders as their core offering, survey data show.)

Adding a foundational-skills supplement to a core program focused on language development and reading comprehension shouldn’t be a problem in theory, said Conway, the Pentucket assistant superintendent. The two work on developing different skills, he said.

But there’s a problem if the core program undermines a structured, systematic approach to phonics instruction, Conway said. He’s seen districts adopt a phonics program but then continue to use curricula that teach “three cueing.”

The technique, common in a balanced-literacy approach to reading instruction, encourages students to rely on pictures or syntax to guess at words when they can’t decode them, which undermines the point of teaching students how to map letters to sounds in a phonics program, Conway said. “That’s what I call the balanced-literacy hangover.”