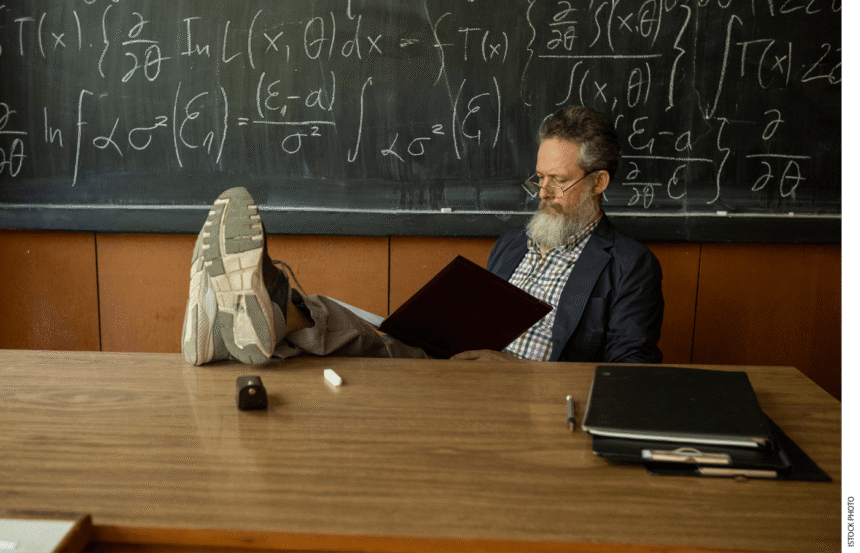

Now, look, I liked the guy. I’ll assume he really is working hard. He didn’t strike me as someone trying to game the system. And yet I found myself wondering how we’ve wound up with this inane system. I mean, Northeastern is, what, the seventh-best research institution in metro Boston? (Off the top of my head, I’d say it trails MIT, Harvard, BU, BC, Tufts, and Brandeis.) Let me be clear—that’s not intended as a knock on Northeastern, given that I think higher ed’s excessive fixation on published research is misguided.

Rather, my point is here we have a highly trained, accomplished, personable guy at a school that’s far better known for its instruction than for its research . . . and yet he barely teaches, nor does he seem to be doing much mentoring or advising. (I’d assume the school’s acclaimed co-op program is placing some number of students in engineering-related jobs, but I could be wrong.) This strikes me as a nutty approach to higher education.

If you want to argue that elite scholars at research universities should be focused on grant-funded research, I’m very sympathetic. I get the argument that teaching loads at the nation’s top 40 or 50 research universities might feature a lot of one-ones for pioneering scholars who are pushing the frontiers of knowledge. But this isn’t that.

This is about the larger political economy of higher education. As Richard Keck and I documented a few months ago, the norm across much of higher education is for faculty to spend most of their time on activities other than teaching. Even at second- and third-tier institutions, faculty are mostly found shuffling papers, sitting in meetings, chasing grants, and publishing trivial, never-read papers in one of the 24,000 barely read journals. This is a story of warped expectations, incentives, and academic culture—one with unfortunate implications for the quality and cost of undergraduate education.

In his terrific book on college teaching, University of Pennsylvania historian Jonathan Zimmerman drily notes that faculty tend to characterize “research as their ‘work’ and teaching as their ‘load’”—a habit that, he observes, speaks “volumes about academic priorities.” Generally, faculty aren’t hired, recognized, or promoted for their teaching. Instead, more and more instruction is off-loaded to an itinerant army of adjuncts and graduate students, few of whom have the incentive or opportunity to maintain rigorous standards or mentor their charges.

Higher education’s apathy about teaching is pretty remarkable. For a sector that assiduously tracks data on enrollment, public spending, faculty positions, and faculty salaries, there’s a remarkable degree of disinterest in what its professors actually do. The University of Delaware administers the annual National Study of Instructional Costs and Productivity, surveying faculty and teaching assistants about course loads and enrollment—but the data are only available to officials at four-year, non-profit colleges. Did I mention the study is being discontinued? Oh, and the existing data are being taken down this December.

The U.S. Department of Education used to track faculty workloads through the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF) but stopped doing so in 2004. Last year, a search for the terms “faculty teaching loads,” “college course load,” “teaching load,” “professor course load,” “professor schedule,” and “faculty load,” yielded zero results on the sites for organizations including the Institute for Higher Education Policy; the Association for the Study of Higher Education; the Stanford Institute for Higher Education Research; the Center for Studies in Higher Education at the University of California, Berkeley; and the Institute for Research on Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

While there’s a dearth of good data, the available evidence suggests the de-emphasis on teaching stretches beyond the one-quarter of higher education institutions that bill themselves as research-oriented. As Colorado State University’s Kimberly French and several colleagues have observed, “Even within teaching-oriented institutions, faculty are increasingly research productive, in an effort to generate funds and emulate the professional status awarded to their colleagues in research universities.” One of the few studies to examine faculty work, carried out by Joya Misra and three colleagues, found that tenure-track faculty reported spending just 27 percent to 35 percent of their working hours on instructional tasks.