Increasing the Benefits

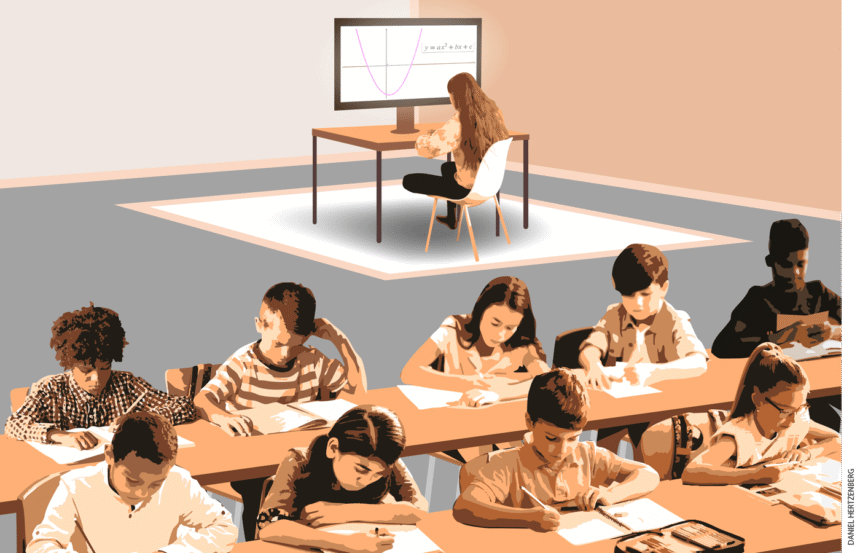

Representatives of some digital platforms admit that boosting student engagement is an ongoing challenge.

Kristen Huff, head of measurement for Curriculum Associates, the company that developed and administers i-Ready, called it a “critical problem.” i-Ready serves 14 million students nationwide, and Huff said the firm recommends its math product Personalized Instruction, which provides individualized lessons and activities online, as an in-class companion to core instruction. An internal study showed that students in kindergarten through 8th grade who used this i-Ready component for 30 to 49 minutes a week for 18 weeks out of a 36-week school year achieved significant growth in math. In the early grades, about 60 percent of students met the recommended amount of practice time; by middle school, that number dropped to around 40 percent.

To help schools get the most out of these programs, the company provides a range of support, including ongoing training and coaching for implementation, a detailed “success guide,” and troubleshooting. Close to 40 percent of the staff work solely in schools and classrooms, Huff said, hoping to have a “constant feedback loop” going with educators.

“When we see schools who are not meeting our recommended implementation, we have a few themes that we work with them on,” she said. “Building community and culture, just really helping every person in the system—district, principal, classroom teacher, instructional coach, parent, student—understand why, when you’re sitting in front of the computer working on a lesson, it’s actually a part of the classroom theory of action.”

Trainers work with schools and staff on how to incorporate the digital lessons and practice into what teachers are already doing, Huff said. But not all students will use it as intended. Students who are the most behind—those in “Tier 3,” in classroom parlance—often aren’t using digital platforms because they are the ones most likely to be pulled for small-group or individual intervention with a teacher. These students often aren’t proficient enough to be “let loose” on digital practice.

Some platforms are looking at how to combine the best of all worlds—the benefits of paper and pencil, digital tools, and teacher input. ASSISTments, a free, independent digital math tool created by a researcher and his wife, allows teachers to select, create, or assemble digital problem sets for students. Teachers can make individual assignments for the whole class, a subgroup of students, or individuals—but all assignments are chosen or created by educators, not an algorithm. In many ways, said co-executive director Britt Neuhaus, their biggest competition is the traditional worksheet. “Who has time to grade worksheets every day?” Neuhaus said. “It is creating more value for the teacher.”

“If today the teacher is teaching ratio, for example, they make a decision: make the assignment in ASSISTments that’s about ratio or something focused on prerequisite knowledge to ensure students can learn ratio right,” said Mingyu Feng, research director of learning and technology at WestED, which performed an independent study of the platform.

The ASSISTments platform still offers the best benefits of technology—for example, students get immediate feedback on whether answers are right or wrong (unless they’re working on open-response problems)—and they can’t move on until they’ve solved the problem correctly.

The platform provides hints on how to tackle a problem if needed, and it produces several kinds of reports for educators, including one showing how students performed on each problem. This allows teachers to tailor future instruction and practice based on how students actually performed on the homework.

For a fee, teachers can also receive professional development and coaching on how best to implement the platform as part of core instruction. But the teacher is still in the driver’s seat when it comes to what material the students are working on digitally. The point of the platform is to closely link teachers’ classroom decisions for their students to data that can support their next instructional move, Feng said. “It’s mentioned a lot in math education that teachers should do data-driven instruction. But without support from computers, it’s pretty hard.”

Feng and her team performed a three-year, randomized controlled trial of the ASSISTments platform as a homework intervention for middle schoolers across two states. Students using the digital homework designed by the teacher performed significantly better in math than students in the control group—not just that year, but in the following years as well.

The nonprofit behind the platform, says that ASSISTments is currently serving about 100,000 students in all 50 states—a small share compared to the massive reach of the popular algorithm-based platforms. Up until two years ago, when the developers began a more formal outreach program to districts, ASSISTments had relied solely on teacher word of mouth, Neuhaus said.

Often, research-based tools don’t have marketing teams behind them, says Feng, and developers struggle to get the word out even when the product has demonstrated its effectiveness in helping students learn.

“The user interface of the platform wasn’t as polished by designers as some long-standing, commercially available tools,” Feng said. “That’s a common issue with products made by researchers. The product is much improved now and is integrated with commonly used learning management systems like Google Classroom or Canvas.”

Kane, the 7th-grade teacher from Colorado, has found his own digital solution, similar to ASSISTments—DeltaMath. Nearly all of Kane’s students are behind in math, and he feels that creating his own digital problem sets allows him to customize them to students’ needs. But he also relies on a much older form of technology.

“Digital can often be hard and unreliable—students will lose their charger, or whatever. They’ll do it for five or seven minutes, get a dopamine boost from watching the problems disappear from the screen. With some exceptions, most 7th-grade math skills require a pencil and paper.”