Now, it seems plans to demolish the fountain, which ran dry again in June 2024 after its final working pipe gave out, might finally come to fruition.

In November, then-Mayor London Breed announced that Embarcadero Plaza would undergo a $25 million transformation, connecting it to the adjacent Sue Bierman Park and creating a 5-acre public square across from the Ferry Building.

The news spurred speculation about the fate of the fountain, which wasn’t included in any of the drafted renderings. Vaillancourt, 96, traveled to San Francisco to advocate for his work’s restoration in the spring, but last month, the Recreation and Parks Department confirmed his supporters’ fears, formally requesting permission to remove the fountain from the city’s Civic Art Collection.

In a letter sent to multiple departments last month, Vaillancourt demanded the city cease and desist all efforts to remove his work, and his attorneys say that they — along with a coalition of preservation groups — will take further legal action if needed.

Also ready to jump into the fight are skaters such as Barrow, who said the fountain is integral to a history the city shouldn’t be so quick to forget.

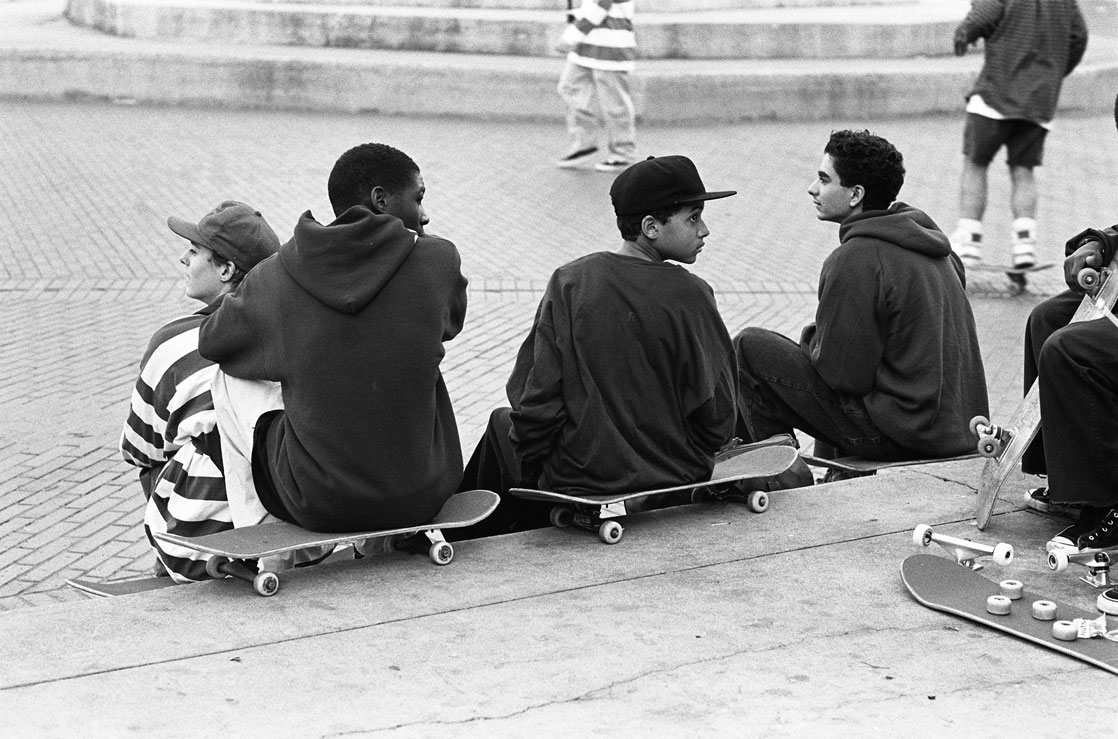

The EMB Crew

Barrow remembers watching skate videos featuring Embarcadero Plaza with Vaillaincourt Fountain looming in the background.

“I fell in love with San Francisco through those videos, and I’m not alone,” he said. “Every city has these great attractions, and they’re not always what they were intended to be. I think this is one of those things, and it’s kind of appalling to me that they’re even considering destroying this.”

Barrow explained that before the late ’80s, people mostly skated in empty backyard pools, skate parks or on wooden half-pipes.

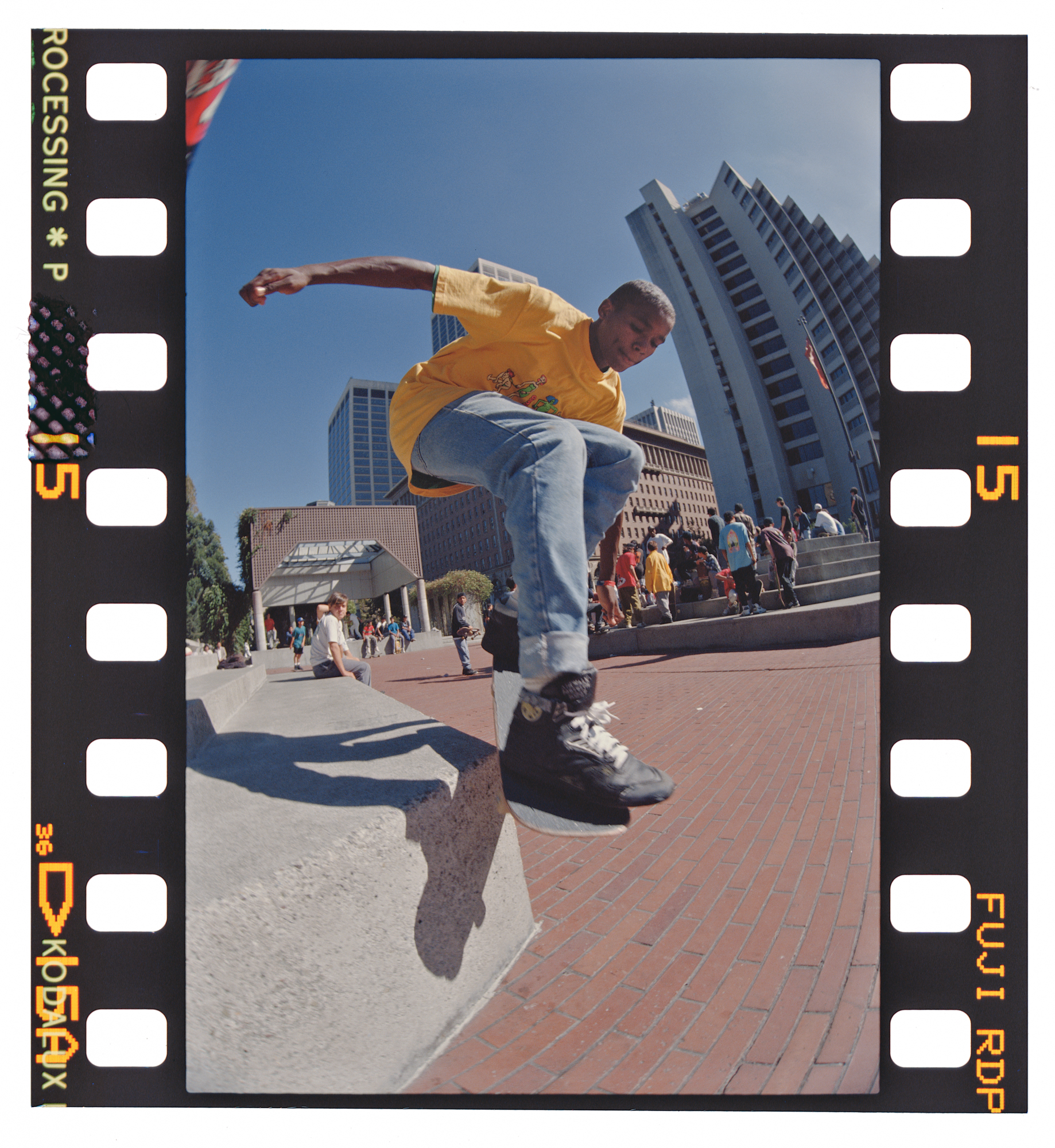

Street skating as a style was developed at EMB.

“That is factual,” Watson said.

Skaters who had popularized “sidewalk surfing” in the 1950s were aging and retiring. Meanwhile, a younger generation — galvanized in part by Michael J. Fox’s skateboard chase in Back to the Future — were arriving on the scene.

“Towards the end of the 1980s, street skating as a way of skateboarding started to develop,” Barrow told KQED. “It embraced the non-purpose-built urban environments — so stairs, ledges, what we call gaps, [or] spaces between two blocks of concrete, and smooth surfaces all started to appeal to skateboarders in a certain way. And Embarcadero had those obstacles.”

Jacob Rosenberg, who describes himself as a more talented filmmaker than skater, spent his teenage years at EMB with a camera, recording young skaters as they invented new tricks and nailed elaborate lines.

Like many Bay Area kids at the time, he said, he didn’t feel connected to mainstream culture of the ’90s. But in skating’s “EMB crew,” he found a sort of unique, welcoming fringe community.

“It was really where I felt a sense of purpose with my camera for the first time, where I kept coming back and I kept filming the same people, and I watched the culture and the tricks of skateboarding transform right in front of me … in the lens of my camera,” he said. “Those of us who were a part of Embarcadero in the late ’80s and early ’90s … we felt so connected to each other and to skateboarding there, maybe more than any other time in our lives.”

Vaillancourt’s brutalist fountain, he said, was the backdrop. Now it’s a relic of that era.

“The fountain is this anchor,” he told KQED. “You can’t skate the fountain, but if you were telling someone about the Embarcadero, you’d say, ‘It’s the place with the bricks, with the fountain.’”

It was featured in the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater video game, and inspired a movement of urban skating that spread as far as Barcelona and Berlin.

People from all over the world came to San Francisco to skate the iconic wave, and in the years since, generations of skaters have returned to the plaza where spots like Mark Gonzalez’s “The Gonz Gap” were made famous.

‘That’s the skateboard experience’

Despite the fountain’s storied history, the skaters say they aren’t really surprised it seems overlooked in the plans for the new plaza.

“That’s kind of the skateboard experience,” Rosenberg said. “They’re not taken seriously, they’re sort of looked down upon.

“For the city to take something that really is an incredible place to celebrate, a very rich and unique history that San Francisco should really own … to treat that in a dishonest way is a real irony,” he continued. “As a skater, you’re like, ‘Of course that was what was going to happen.’”

San Francisco’s Arts Commission is expected to consider the Recreation and Parks Department’s request to remove the Vaillancourt Fountain this fall. Rec and Parks officials estimate that to restore it would cost $29 million.

If the commission does approve the teardown, it could still be stalled by legal action.

Vaillancourt’s son Alexis told KQED his father’s attorneys have gotten no response to the cease and desist letter sent to multiple city departments, as well as BXP, the private development company handling the renovation, on Aug. 29.

He believes further litigation, like a request for an injunction, will likely be necessary.

The city attorney’s office said departments are still reviewing their next steps and no final decision has been made.

But in an email, office spokesperson Jen Kwart called the fountain “a structurally unsound, hazardous structure with no viable path forward short of a multi-million dollar renovation. That’s before considering its long-term maintenance and seismic vulnerability.”

In addition to high renovation and restoration costs, it’s also been maligned as a place unhoused people have used to rest or bathe and is seen by many as an eyesore synonymous with the city’s struggling downtown.

Barrow pointed out that that’s not too dissimilar from the context in which it rose to now-nostalgic fame.

“The early ’90s was a pretty fraught time — just like ours — when it came to fear of cities and fear of youth subcultures,” he said. “Street skating in San Francisco … showed a very diverse group of skateboarders skating in an urban place. Skateboarders had kind of figured out how to be in a city and how to create a community in this era when there was a lot of fear.”