After graduating from Knox College in Illinois with a bachelor’s degree, Stephanie Martinez-Calderon’s plans were upended by the pandemic. She hadn’t planned on becoming a teacher but found an opportunity to tutor remotely for the year after college.

Tutoring helped her build confidence and develop instructional skills, and today she’s a middle school teacher in the Washoe County School District in Nevada.

Tutoring can be a powerful training ground for future educators, providing hands-on experience, confidence and a bridge into the classroom. And what might begin as a temporary opportunity can become a career path at a time when teachers are needed more than ever: A recent report noted that nearly one in five K-12 teachers plan to leave teaching or are unsure if they’ll stay.

Turnover remains a crisis in many districts, one that can be solved by a ready-made pipeline of young future educators with instructional experience and relationship-building skills they’ve gained from tutoring.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

How school districts think about tutoring should evolve. Rather than seeing it as a short-term response to pandemic-interrupted learning, they should view it as part of the fabric of school design and future educator development. This requires including tutoring in strategic plans, forming community partnerships and creating a structure to sustain programs that cultivate tutors for careers in education. To fund these programs and pay tutors, districts can redirect Title I funds, use federal work-study and create apprenticeship programs.

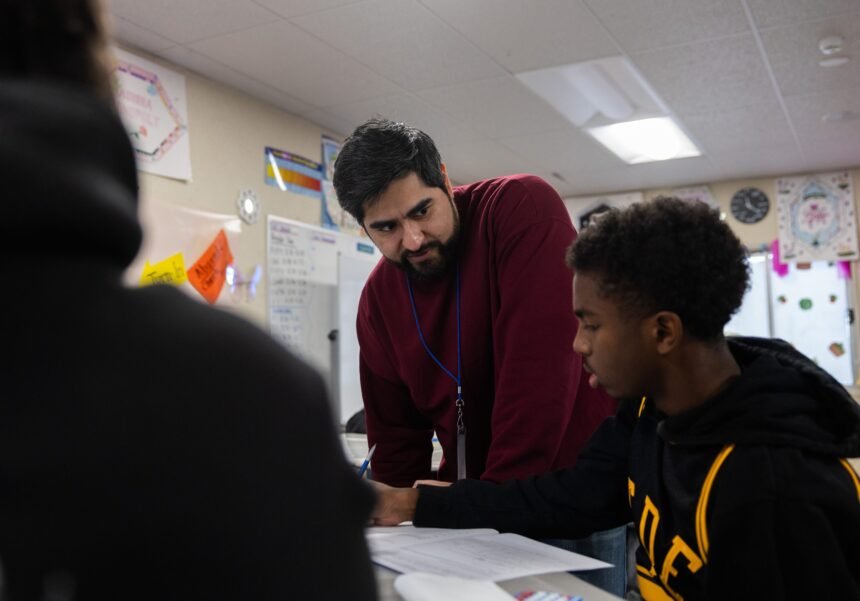

Starting as a tutor allows aspiring educators to build core teaching skills in a supportive, lower-stakes environment. Tutors learn to navigate student relationships and adapt lessons to individual needs. Without having to manage an entire classroom, they can practice asking questions that get students thinking and selecting problems to help students learn. This early practice eases the transition into teaching.

Tutors from Generation Z, born between 1996 and 2012, often bring fresh energy to the profession. As digital natives, they are reimagining how to engage and inspire students, leverage technology and foster creativity and new approaches to learning.

They are also the most ethnically and racially diverse generation yet: Many come from backgrounds historically underrepresented in the teaching force; over half of undergraduates identify as first-generation college students. Their engagement broadens the prospects for a more diverse teacher pipeline.

Tutor recruiters have noticed that Gen Z workers don’t just want a job — they want roles committed to social impact, professional growth and sustainable work-life balance.

Gen Z’s emphasis on flexibility and remote opportunities is one of the most significant workforce changes since the pandemic. They value mental health, stability and mission-driven work. Part-time, hybrid and wellness benefits help recruit young talent.

At our nonprofit, recruiters hear from education candidates that Gen Z appreciates the chance to try out industries, and that tutoring provides them with a window into the world of teaching.

Public schools could better meet the evolving needs of young professionals entering education by reimagining tutor roles to include hybrid options, mental health supports and collaborative teaching pathways for professional growth. For instance, a tutor might start off working in a part-time online tutoring role, but after interacting with students virtually and gaining more experience, they may be more excited to take on a full-time teaching role on-site.

For school districts, tutoring programs can serve as effective recruitment pipelines. By offering recent graduates a low-barrier entry point into education — one that doesn’t require immediate certification — districts can spark interest in teaching among candidates who may not have previously considered it.

Amid ongoing hiring challenges, particularly mid-year vacancies, tutors can offer timely solutions.

When tutors step into teaching roles, they bring valuable continuity — familiarity with the students and insight into progress and school culture. This seamless transition supports both student learning and district staffing needs.

Related: PROOF POINTS: Taking stock of tutoring

The idea that tutoring should be built into future educator pipelines is spreading. For example, since the launch of its Ignite Fellowship in 2020, Teach for America says that 550 of its former tutors have become full-time teachers. The program has proven to be especially effective at drawing in nontraditional candidates — those who may not have initially envisioned themselves in the classroom. In Washington, D.C., the school district launched a tutor-to-teacher apprenticeship program after success with high-impact tutoring. In Texas, teacher residents are required to work as tutors and in other support roles while co-teaching with a mentor.

By offering flexible, purpose-driven opportunities, districts can attract Gen Z professionals and give them a meaningful entry point into teaching. And tutoring programs can become more than academic support — they can serve as strategic talent pipelines that strengthen the future of the teaching workforce.

Alan Safran is co-founder, CEO and chair of the board of Saga Education; Halley Bowman is senior director of academics.

Contact the opinion editor at opinion@hechingerreport.org.

This story about tutoring was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.