The Enduring Value of Problem Solving

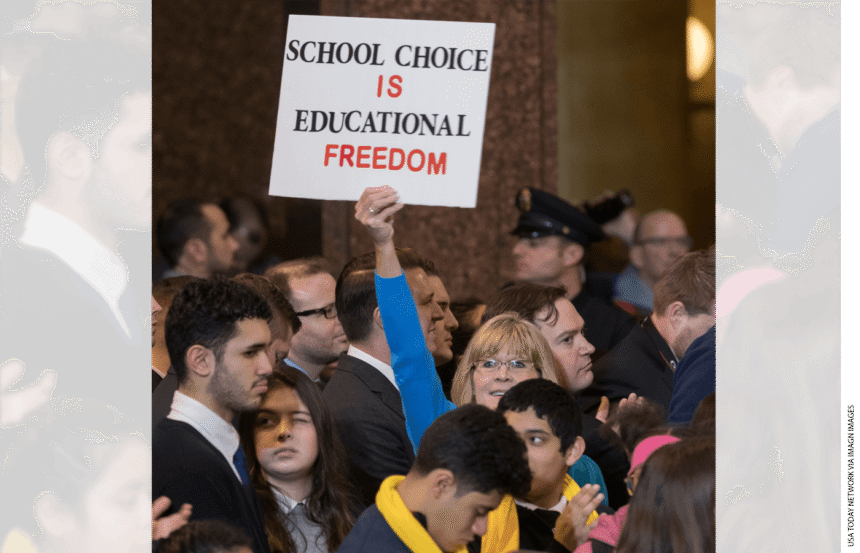

Proponents have long argued that school choice will unleash a virtuous cycle of innovation and improvement as new operators gain the freedom to test promising new ideas, while families use their enrollment decisions to reward and punish providers based on the value of their offerings. Milwaukee shows that there is some truth to this theory: Private-school choice programs do, in fact, unleash the entrepreneurial impulses of private actors and create opportunities for families to “vote with their feet.” But this bargain comes with unexpected costs—widespread school failure—and may fail to catalyze the very thing many proponents of school choice hope for: systemic improvement.

While private-education choice in Milwaukee hasn’t instigated largescale, systemwide improvement—student outcomes remain stubbornly low across all three school sectors—it’s hard to deny that some families have used the program to access better schools. As Fuller put it 25 years after he succeeded in securing vouchers for the city, “There are thousands of Black children whose lives are much better today because of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. They were able to access better schools than they would have without a voucher.” Capitalizing on these gains so all families have access to schools that enable their children to succeed is the central challenge for Milwaukee and any city that hopes to improve educational opportunity.

Milwaukee’s experience suggests that catalyzing the creation of good new schools may take more than simply subjecting public education to the discipline of the marketplace. As Borsuk and Carr concluded in their early analysis of the voucher program’s results, “Creating a new school through the choice program is easier than most people expected. Creating a good new school is harder than most thought it would be.”

Top-down accountability pressures produced some good results in Milwaukee—eliminating the worst performing operators and raising the floor on performance citywide. But such pressure has proved a limited tool when it comes to producing more of the schools families want and children’s futures depend on.

If neither free markets nor top-down accountability on their own can solve the challenges that face public education, it is incumbent upon policymakers and those that influence them to devise other, complementary strategies. What this will look like in practice isn’t entirely clear, but Milwaukee’s experience provides clues.

In a city that provided nearly limitless opportunities for entrepreneurs to build education alternatives and for families to choose them, it’s remarkable that the most successful schools—and those that have endured the longest—all seemingly emphasize traditional teaching methods and complementary student supports long considered to be hallmarks of a good education. But today’s most celebrated entrepreneurs have increasingly rejected these conventional notions of “good” education, choosing instead to wrap themselves in the cloak of progressive education, where the child’s interests and instincts are the best and only guide to authentic learning. Philanthropists have contributed to the fervor over these alternatives, which are often celebrated as “new” even though they embrace the antique ideas of John Dewey and the storied Summerhill School, founded in 1921. Whether the schools families most want will succeed in securing the investment they need will hinge on closing this disconnect.

Many of the schools that have risen to the top of the education marketplace in Milwaukee also benefited from aligned ecosystems of support, suggesting such structures will be enduring features of education even in systems that rely more on private provision. Catholic and Lutheran schools have counted on resources from their respective faith communities, including donations and affiliated teacher preparation programs. Local philanthropists, too, have played critical roles, helping to launch new schools and strengthening those that may have otherwise struggled. Their investments shaped the trajectory of many of Milwaukee’s best private and charter schools. They could have a hand in shaping the private-education market in other cities and states.

These ideas may not generate the same snappy sound bites found in debates about school choice or test-based accountability, but local civic leaders believe they are essential to strengthening public education in Milwaukee. As the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce put it in a recent report, “We are asking schools to climb a Mt. Everest-sized challenge . . . and to do so without the oxygen of resources.”

Closing this resource gap in ways that catalyze improvement across public, private, and charter schools is far from straightforward, but there are glimmers of hope on the horizon. The city successfully lobbied state legislators to secure more public investment in its schools, motivated by what local education leader Brittany Kinser called the “harsh realities of running an underfunded school.” Both publicly and privately operated schools are targets of a new statewide initiative designed to improve the quality of reading instruction.

Agents of civil society—nonprofits and local journalists—have played important complementary roles in improvement. Pioneering reporting by journalists such as Sarah Carr, Alan Borsuk, and Erin Richards (all through the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel) was critical to exposing the on-the-ground realities of Milwaukee’s experiment in private-education choice and catalyzing policymakers’ work to improve it. Today, City Forward Collective has taken up that mantle, working with local and state leaders to help Milwaukee families secure the educational opportunities they deserve. Other nonprofits have stepped in to strengthen the enabling conditions—like access to well-prepared teachers—that all good schools, regardless of sector, depend on.

The failure of vouchers to provide deliverance to Milwaukee’s system of publicly funded education reminds us that simple theories of action rarely provide reliable mechanisms for solving complex problems. In 1993, just three years into Milwaukee’s experiment with private-school choice, Fuller poignantly observed that “it is easier to wage revolution than it is to govern. . . . When you get in and you start trying to govern, you can no longer have the narrowest view because you got to now deal with a whole bunch of other issues and realities.”

While school choice may have failed to deliver all that its proponents hoped for in Milwaukee, the city’s experience makes clear that the results of any initiative depend more on continued problem solving than on unbending ideological commitments. Today’s school choice supporters would be wise to heed this lesson.